Science: the final frontier. These are the voyages of Vicky Steeves. Her nine-month mission: to explore how scientific data can be preserved more efficiently at the American Museum of Natural History, to boldly interview every member of science staff involved in data creation and management, to go into the depths of the Museum where none have gone before.

Hi there. Digital preservation of scientific data is criminally under-addressed nationwide. Scientific research is increasingly digital and data intensive, with repositories and aggregators built everyday to house this data. Some popular aggregators in natural history include the NIH-funded GenBank for DNA sequence data and the NSF funded MorphBank for image data of specimens. These aggregators are places where scientists submit their data for dissemination and act as phenomenal tools for data sharing, however they cannot be relied upon for preservation.

Science is, at its core, the act of collecting, analyzing, refining, re-analyzing, and reusing data. Reuse and re-analysis are important parts of the evolution of our understanding of the world and the universe, so to carry out meaningful preservation, we as the digital preservationists need to equip those future users with the necessary tools to reuse said data.

Therein lies the biggest challenge of digital preservation of scientific data: the very real need to preserve not only the dataset but the ability to deliver that knowledge to a future user community. Technical obsolescence is a huge problem in the preservation of scientific data, due in large part to the field-specific proprietary software and formats used in research. These software are sometimes even project specific, and often are not backwards compatible, meaning that a new version of the software won’t be able to open a file created in an older version. This is counter-intuitive for access and preservation.

Digital data are not only research output, but also input into new hypotheses and research initiatives, enabling future scientific insights and driving innovation. In the case of natural sciences, specimen collections and taxonomic descriptions from the 19th century (and earlier) are still used in modern scientific discourse and research. There is a unique concern in digital preservation of scientific datasets where the phrase “in perpetuity” has real usability and consequence, in that these data have value that will only increases with time. 100 years from now, scientific historians will look to these data to document the processes of science and the evolution of research. Scientists themselves will use these data for additional research or even comparative study: “look at the population density of this scorpion species in 2014 versus today, 2114, I wonder what caused the shift.” Some data, particularly older data, aren’t necessarily replicable, and in that case, the value of the material for preservation increases exponentially.

So the resulting question is how to develop new methods, management structures and technologies to manage the diversity, size, and complexity of current and future datasets, ensuring they remain interoperable and accessible over the long term. With this in mind, it is imperative to develop an approach to preserving scientific data that continuously anticipates and adapts to changes in both the popular field-specific technologies, and user expectations.

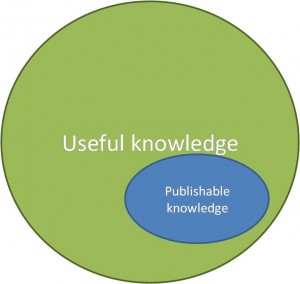

Published data aren’t the end-all-be-all of digipres for science. There are a lot data that need our help! http://www.opensciencenet.org/

There is a pressing need for involvement by digital preservationists to look after scientific data. While there have been strides made by organizations such as the National Science Foundation, Interagency Working Group on Digital Data, and NASA, no overarching methodology or policy has been accepted by scientific fields at large. And this needs to change.

The library, computer science, and scientific communities need to come together to make decisions for preservation of research and collections data. My specific NDSR project at AMNH is but a subset of the larger collaborative effort that needs to become a priority in all three fields. It is the first step of many in the right direction that will contribute to the preservation of these important scientific data. And until a solution is found, scientific data loss is a real threat, to all three communities and our future as a species evolving in our combined knowledge of the world.

I will leave you, dear readers, with a video from the Alliance for Permanent Access conference in 2011. Dr. Tony Hey speaks on data-intensive scientific discovery and digital preservation and exemplifies perfectly the challenges and importance of preserving digital scientific research data: