Welcome, dear readers! I’m Morgan McKeehan (@anyformation), NDS Resident at Rhizome, an internet-based arts organization dedicated to supporting the creation, distribution, and critical reception of artworks engaged with technology and digital cultures. My project focuses on preserving artworks within Rhizome’s online archive (project description at NDSR-NYC), using new methods and tools developed by the organization and its partners. I will also assist with the migration of Rhizome’s ArtBase of more than 2000 works to a new Wikibase system, and will establish standardized criteria and metadata describing levels of access quality to support preservation workflows across the entire collection.

Given my project’s focus on born-digital artworks, I felt especially fortunate to begin my residency by attending a recent symposium and workshop at the Guggenheim Museum, Techfocus III: Caring for Software-based Art (TF3). The third installment in the TechFocus series, which was initiated in 2010 by the Electronic Media Group within the American Institute for the Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works (AIC), TF3 brought together conservators, curators, archivists, art historians, artists, and computer scientists, providing in-depth discussion, hands-on instruction, and excellent context for many of the challenges I’ll be addressing over the course of my residency.

A hands-on programming workshop was a highlight of TechFocusIII. photo by @rchiango

Conservation for time-based media art faces a range of challenges common to preservation for digital objects overall, as described in an interview with Joanna Phillips, Conservator of Time-Based Media at the Guggenheim: “Time-based media works are unstable by nature: their technological constituents become obsolete, they frequently require adaptation to changing installation environments, and every reinstallation introduces some extent of interpretation.” When shaping the specific relationships between form and content in an artwork, this interpretive aspect of preservation arguably takes on particular significance, and demands careful consideration and skillful work by conservators.

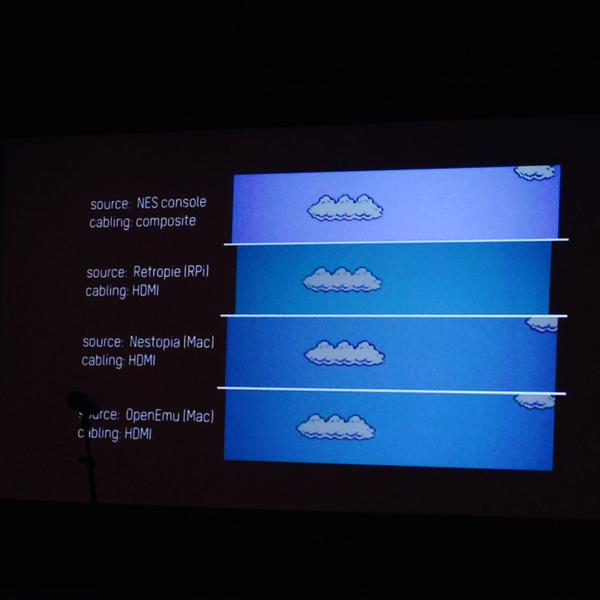

A presentation slide by Agathe Jarczyk analyzed variability of a/v output for Cory Arcangel’s Super Mario Clouds (2002). photo by @sarahecook

The TechFocus series was organized by art conservation practitioners to equip collection professionals for this demanding role by sharing best practices, documentation, and instruction focusing on a specific area of technology. The series’s first installment marked the 10-year anniversary of the TechArchaeology symposium at SFMOMA in 2000, a significant early moment in the developing conversation about how to approach the long-term care of time-based art. Many of the discussion points highlighted at TF3 demonstrated effective conservation approaches for addressing key questions explored in TechArchaeology:

- How can conservators identify and define the significant properties of artworks as complex digital objects? Is it possible to define what is at the “core” of an individual work?

- What kind of documentation for artworks and for preservation processes can best establish and communicate these properties, to ensure accurate representations of the artwork in the future?

- What role can artists play in the work of conservators and curators responsible for preserving and exhibiting variable works?

Case studies presented over the course of TF3 provided concrete examples of how current preservation work addresses these questions to increase the range of approaches to inherently variable objects. A study of John Gerrard’s Sow Farm (near Libbey, Oklahoma) (2009) at the Tate in London weighed the merits of virtualization for presenting a work that is exceptionally demanding of computational resources; Sow Farm uses 3D modelling to create a simulated representation of an agricultural complex and surrounding landscape over 365 days, unfolding in real time. A detailed look at MOMA’s exhibition of Feng Mengbo’s Long March: (Restart)(2008) touched on the benefits of building of an exact replica of the original hardware configuration provided by the artist, to simplify the preservation of software interactions within the machine. A presentation about the code analysis performed by students working with Deena Engels in NYU’s Computer Science, Web Programming and Applications program revealed how investigating the artwork’s “digital anatomy” allowed conservators to make Siebren Versteeg’s Untitled Film 2, in the collection of the Guggenheim, less vulnerable to link rot by providing insight into the work’s data sources.

The potential benefits of ongoing dialogue between artists and conservation staff was described especially vividly in reflections on SFMOMA’s use of version control via github for documenting and exchanging ideas with the artist Jurg Lehni as the museum prepares to exhibit his drawing machine, Viktor, when SFMOMA reopens next year.

Martina Haidvogl shared her experience of the collaborative process and information exchange between SFMOMA and Jurg Lehni. photo by @juerglehni

Additionally, hands-on sessions in day two of TF3 provided instruction in practical skills for working with software-based art, including using version control, creating disk images and using emulation to access stored disk images, and writing code with Processing, a visual programming language created by artists Ben Fry and Casey Reas in 2001. Exceptionally well-organized documentation distributed in advance of the event prepared attendees to install needed software on their own computers and make the most of the limited time available.

The depth of these studies in preservation within the museum environment provided an illuminating perspective to bring to the different scale and character of Rhizome’s collection. A presentation by Dragan Espenschied, Rhizome’s digital conservator and my NDSR program mentor, emphasized the diversity of works within the ArtBase given the size of the collection, the collection’s origin and growth as a resource contributed to and mediated by the online community, and the inherently variable nature of individual web-based works created to perform on different browsers across operating systems. Many of the works in the ArtBase were created on the fly to run wherever; the contemporary stewards of a collection reflecting the spontaneity, diversity, and sprawl of the web need to implement alternative methods to develop sustainable preservation workflows—especially given the organization’s small size and limited resources.

Dragan Espenschied discussed the complexity involved in sustaining functional access to artworks residing on social media sites such as Instagram. photo by @genevieve_hk

Fortunately, Rhizome’s conservation program benefits from deep roots in online culture, and partnerships formed to develop adaptable tools for complex digital objects. During my residency I will use Webrecorder, a new tool providing high-fidelity web archiving which allows for capturing dynamic web sites at a much greater level of detail and functionality than has previously been possible, to preserve externally-linked works within the ArtBase that are currently at a high risk of disappearing. We will be able to generate detailed metadata on filetypes even within these archival copies by using Siegfried, a freely available file format identification tool, which has recently added the capability to extract PRONOM data within WARC files.

NDSR-NYC alum Karl-Rainer Blumenthal @landlibrarian is also excited about Siegfried and WARCs

I’ll also work on providing ready online access for artworks in Rhizome’s collection which cannot run on current software, using a cloud-based emulation service (EaaS) developed by the bwfla project. Take a look at this online exhibition of Theresa Duncan’s video games/CD-ROMs to see how Rhizome’s and bwfla’s collaborative work provides visitors with seamless access to artworks by running legacy operating systems right in the browser.

In my next post, I’ll explore EaaS in more detail as I prepare for a panel on emulation as an access tool for digital preservation, organized by Julia Kim, 2014-15 NDS Resident at NYU libraries, at the upcoming AMIA conference in Portland, OR. Looking ahead to this event, it’s very exciting to have the opportunity at Rhizome to build on the accomplishments of the previous NDSR-NYC cohort and the contributions of the NDSR program to the field of digital preservation as a whole.