Peggy here! My last post made the case for detailed audiovisual materials while also pointing out the problems this causes with interoperability. In this post, I will survey some of the options for audiovisual metadata. If you have any recommendations for standards not mentioned here, please do share in the comments. My work at the Museum of Modern Art has allowed me to do in-depth research on existing standards for recording metadata about audiovisual objects. Metadata for audio and moving images requires a very granular level of detail due to the complex nature of the objects themselves. In order for proper preservation and playback of these materials, information about characteristics such as frame rate, sampling rate, signal type, aspect ratio, number of channels, etc. must be recorded in as much detail as possible. Because of this, audiovisual metadata standards tend to be very lengthy, complex, and, at times, difficult to fully conceptualize. However, even A/V novices like me will be able to understand how to apply these standards if the time is taken to study them. It also doesn’t hurt to ask your A/V expert colleagues for help understanding what the heck words like “endianness” mean.

AES-57 2011: This standard was developed by the Audio Engineering Society to provide highly detailed information about audio materials. As video is completely outside the scope of this standard, it is not sufficient for describing audiovisual materials. However, I believe that much can be learned from the effort that went into designing this schema. It is highly technical and allows for a great amount of detail. The considerations that were made for what to include in this standard and how to arrange relationships among elements could inform decisions about how to organize metadata for video collections. For example, it could provide ideas for how to relate things such as tracks, channels, codecs, and formats to their parent digital object. Plus, if you can understand all the technical terms in this standard, you are well on your way to a/v domination.

MPEG-7: This standard allows for extremely detailed recording of technical metadata as well as rights metadata and descriptive metadata for the intellectual content of the materials. MPEG-7 is very technical and complex, and for these reasons would likely not be a good first choice for institutions just starting out with audiovisual metadata. However, it is a very powerful tool for preservation for those institutions with the resources and expertise to properly leverage it.

PBCore: PBCore was designed to allow public broadcasters to describe their audiovisual collections. Despite the fact that it was intended for public broadcasters, that intended audience does not mean other potential users such as libraries or archives should be wary of using this standard for their audiovisual collections. PBCore allows for relatively detailed technical metadata as well as descriptive and rights metadata, so it offers a very comprehensive framework for describing audiovisual materials. It is also relatively easy to understand, as it does not use a lot of highly technical language. Another benefit to using this standard is that even if extremely granular technical detail is needed, it is very easy to insert XML extensions of other schemas into PBCore.

reVTMD (schema only, no documentation): This is an emerging standard designed by NARA to describe the process history of digitizing audiovisual materials. It allows for detailed technical description of every piece of hardware and software used in the digitization chain, as well as the role that each tool played. However, it has not been widely documented or adopted as of yet; its main use is as an extension in other schemas, as it is really the only existing schema that allows for technically detailed process history metadata.

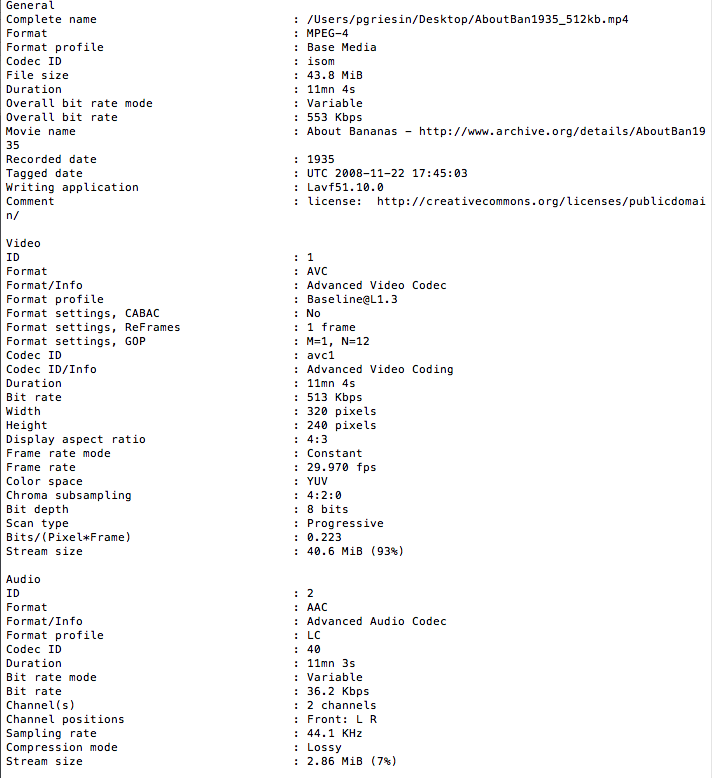

videoMD: VideoMD was designed by the Library of Congress to provide technical metadata about video objects. It allows for a great deal of granularity and is a good choice for institutions that simply wish to describe technical information at the object level, rather than creating complex relationships between audiovisual objects. It is also perhaps the easiest of the highly technical schemas for the layperson to understand. Much of the information described by videoMD can be automatically extracted from digital objects using programs like MediaInfo and FFprobe, then mapped into a METS file using the videoMD data structure.

MediaInfo output for a digital video file. There’s no need to enter this information manually when you can use simple tools to automatically generate it and avoid human error.

Qualified Dublin Core, MODS, and other general standards: Depending on the needs or size of a collection, highly detailed technical metadata may not be a necessity or, more likely, a possibility. In that case, more traditional bibliographic standards may be appropriate. Although they will not be able to provide much technical metadata, they will be able to provide descriptive information about the intellectual content of the object. This method is not sufficient for sustainable digital preservation because it does not allow for the level of technical granularity necessary for preservation purposes. However, it at least allows for basic descriptive records.

My research has shown me that no single schema seems to fit the needs of a given institution perfectly, and this problem only seems to be exacerbated with audiovisual materials. This is likely a result of the vastly differing needs of institutions that hold audiovisual materials, from small public libraries with a few copies of commercially available DVDs to film repositories that hold thousands of unique and irreplaceable materials in multiple formats. As a result of this complexity, a lot of institutions are forced to be quite creative and innovative with their use of these standards. At the Museum of Modern Art for example, we will likely use some combination of standards such as PBCore and reVTMD as well as PREMIS and METS for recording digitization process history of audiovisual materials. I would be very interested in hearing from readers about how their institutions are managing metadata for their audiovisual collections, as well as standards not listed in this post that would be useful for that purpose.

Great post, Peggy! FYI — a PBCore RDF ontology is also in the pipeline and will likely be launched within the next several months, definitely within the next year.

Thanks Casey! I can’t wait to see that. Should be really interesting!