Happy New Year, Readers!

With 2016 upon us, it seems only natural to recap what we’ve accomplished so far at WCS and meditate on our next steps:

Phase 1

The first part of my project involved conducting in-depth interviews with key staff from three WCS departments participating in the project. The interviews, plus some investigative disk analysis on each department’s networked storage, helped us gain important information about materials created throughout each of their workflows – the media types, data formats, volume and frequency of data creation, software dependencies, and current storage and organizational methods for both active and inactive materials. With this information, I was able to identify the specific needs of the archive for processing these collections and outline a set of functional requirements for the desired digital archiving system in accordance with the NDSA Levels of Preservation (a main goal for this project is to fully meet Level 1, and hopefully Level 2). The functional requirements are being used as a checklist as we compare collection processing software and digital storage options.

Phase 2

Now underway, the second part of my project involves using all of the information gathered during Phase 1 to select test collections of digital materials from each department, develop a standard Submission Agreement for the transfer of these materials to the Archive, and draft guidelines for future submissions.

In a recent meeting, one of my mentors aptly pointed out, “Now this seems like the hard part”, and boy was he right. Although he was likely thinking specifically about materials from his own projects and the geospatial data that poses so many interesting challenges for us, the process of Selection and Appraisal is increasingly complex when considering the important factors that impact how we make decisions going forward. Some of the main issues we need to consider are:

- Volume and complexity of digital materials vs. Archive resources.

- Designation of “active” vs. “inactive” materials.

- Responsibilities of the Departmental staff vs. the Archive in preparing digital materials for transfer.

When deciding on storage options and estimating costs, projected rates of growth of digital materials within various departments were determined based on the average sizes of common data sets and frequency of data creation. With this information, many archives should be able to determine storage requirements and start making decisions about what to collect and when.

However, anticipating growth does not address all of the issues when estimating costs. For example, in regards to geospatial data at WCS, the average size of a shapefile or a geoTIFF does not accurately represent the collection as a whole, since these projects involve other assets such as the development of complex geodatabases. The size of a geodatabase when compressed and exported as a file does not capture the internal relationships, references, and links which comprise the essence of the information. These relationships may include links to online external data sources, or to ever-changing data sets created by other organizations (like annual reports generated by local, state, and federal institutions). So, the questions for us are not just about how big the data is or whether it conforms to a specific geospatial metadata standard, but how the relational data will be preserved. This is especially important, considering that these assets depend and function on some data that is always changing which may require preservation of records that are not created by WCS (and may or may not be preserved elsewhere).

In regards to the identification of “active and inactive” materials, this becomes difficult when, because of improvements in networked storage options, digital files related to ongoing projects can remain on a shared server “indefinitely”, available for access whenever the project needs to be revisited. An example of this at WCS is the Exhibits and Graphic Arts Department (EGAD) department’s collection of files relating to the development of exhibits (read: buildings/structures). While it would benefit WCS for these files to be preserved early on, to document the development and history of the exhibits, the department may need to access these files after years or even decades in order to make changes to exhibits. If the same materials need to be accessed, modified, and remain searchable by the same identifying information (like a project-based folder name known by all members of the department) for several years, and the timeline varies across exhibits depending on trends in attendance or shifting interests / priorities for a zoo, how does an archivist approach the task of developing a retention schedule for this department? More broadly, in the digital age, at what point do “projects” (and their content) become inactive?

Most importantly, I think this calls for some deep discussion about the mission and role of the Archives in an institution like WCS (where there is also institutional back-up of digital materials unrelated to the Library and Archives that may evolve into a larger digital repository of its own), and reassessment about the scope of digital materials to be collected as well as the needs of the designated community.

Questions like these underline the importance of what the Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems (CCSDS) refers to as the “Preliminary, pre-ingest, or pre-accessioning” phase of a digital preservation project, as outlined in the CCSDS’s Producer-Archive Interface Methodology Abstract Standard (“PAIMAS”, ISO 20652:2006) and Producer-Archive Interface Specification (“PAIS”, ISO 20104:2015).

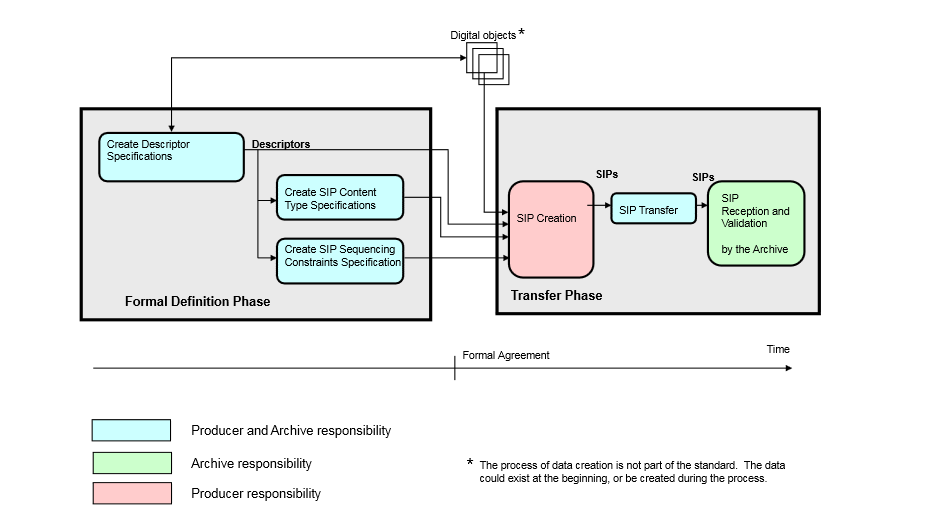

Expanding on the requirements for Ingest and Administration within the OAIS reference model, these two documents aim to “identify, define and provide structure to the relationships and interactions between an information Producer and an Archive,” (PAIMAS) and provide recommendations on the “implementation of… negotiated agreements between the data Producer and the Archive that facilitate production of agreed data by the Producer and validation of received data by the Archive….[and] how these data will be aggregated into packages for transmission…” (PAIS). PAIMAS breaks down the Producer-Archive Interface process into four phases: Preliminary, Formal Definition, Transfer, and Validation.

At this point in my project (partially due to the holiday break), we are in a kind of post-Preliminary-pre-Formal-Definition limbo, in which questions about how to balance basic preservation needs, the needs of the designated community, and the resources of both Archive and Producers are looming over the decision-making process surrounding what precisely we are to collect from each department, and what the responsibilities of each stakeholder include, given all of the technical and contextual information we have from Phase 1. To get right down to it, we’re talking about SIPs.

A high-level view of the Producer-Archive Interface phases, Formal Definition and Transfer with Validation, (PAIS, p. 2-2)

While these standards do provide an excellent framework for approaching the process as a whole, in this case (and I assume many other cases) negotiations about the accepted contents of a SIP are complicated by the limited time and resources of the Producers and their ability to entirely comply with standardized requirements for the creation and arrangement of their digital materials. The OAIS reference model defines a SIP as “an Information Package that is delivered by the Producer to the OAIS…”, but to speak frankly, it seems unlikely that, when given a list of accepted media types and formats for submission to the Archives, all departments at a given institution would have the time or expertise to make sure their collections fit the bill before being regularly transmitted to an Archive. It is more likely that a collection will be transmitted to the archive and then undergo some processing by an archivist in order to ensure a valid SIP.

Does this conundrum call into question the essence of a SIP (Gasp!)? Or does it simply highlight the need for more flexibility to be built into the submission agreement to allow for rearrangement of materials as necessary for creation of AIPs and DIPs?

Nailing down the basic elements of what will be required from each department is essential, and I think this process highlights the importance of close relationships between Producers and Archives as early as possible in the digital lifecycle in order to facilitate smoother submission of collections. As I prepare to finalize decisions about WCS Library and Archive’s SIP requirements and Submission Policies, in advance of configuring a digital archives repository, I’m curious how others have approached this issue.

What challenges do you face in developing Submission Agreements and defining your SIPs? What does a SIP look like for you, and at what point is it created? And do you have any radical methodologies for implementing SIP structure? I would love to hear your ideas and experiences.

Thanks for reading, and be sure to keep your eyes peeled for an upcoming post by Mary Kidd, our NDSR fellow at NYPR, on The Signal!