Hello readers! A few days ago, (Monday, January 25th to be precise), the NDSR NY cohort took a field trip to Princeton, New Jersey to visit Jacob Nadal at ReCAP, the Research Collections and Preservation Consortium, Jean Bauer at Princeton University’s Center for Digital Humanities, and Jarrett Drake, the Digital Archivist at the Seeley G. Mudd Library. For those of you that are unaware of the intricacies of the NDSR program, each resident is responsible for planning an enrichment activity broadly dealing with digital preservation and stewardship. While the New York residents are collectively planning a digital preservation symposium to take place in the spring, April 28th, I also took the enrichment requirement as an opportunity to plan this trip. I really enjoy site visits, and I feel like it provides a richer understanding of the actual labor that archivists do.

ReCAP

How ReCAP works

Our first stop of the day was at ReCAP, the Research Collections and Preservation Consortium, which is run by Jacob Nadal. ReCAP is a storage repository for Princeton University, New York Public Library, and Columbia University, and provides resource sharing services such as Inter-Library Loan (ILL) fulfillment and transit of materials from the storage facility to patrons. ReCAP houses 13 million items from the partner institutions, with the ability to hold millions more in the coming years.

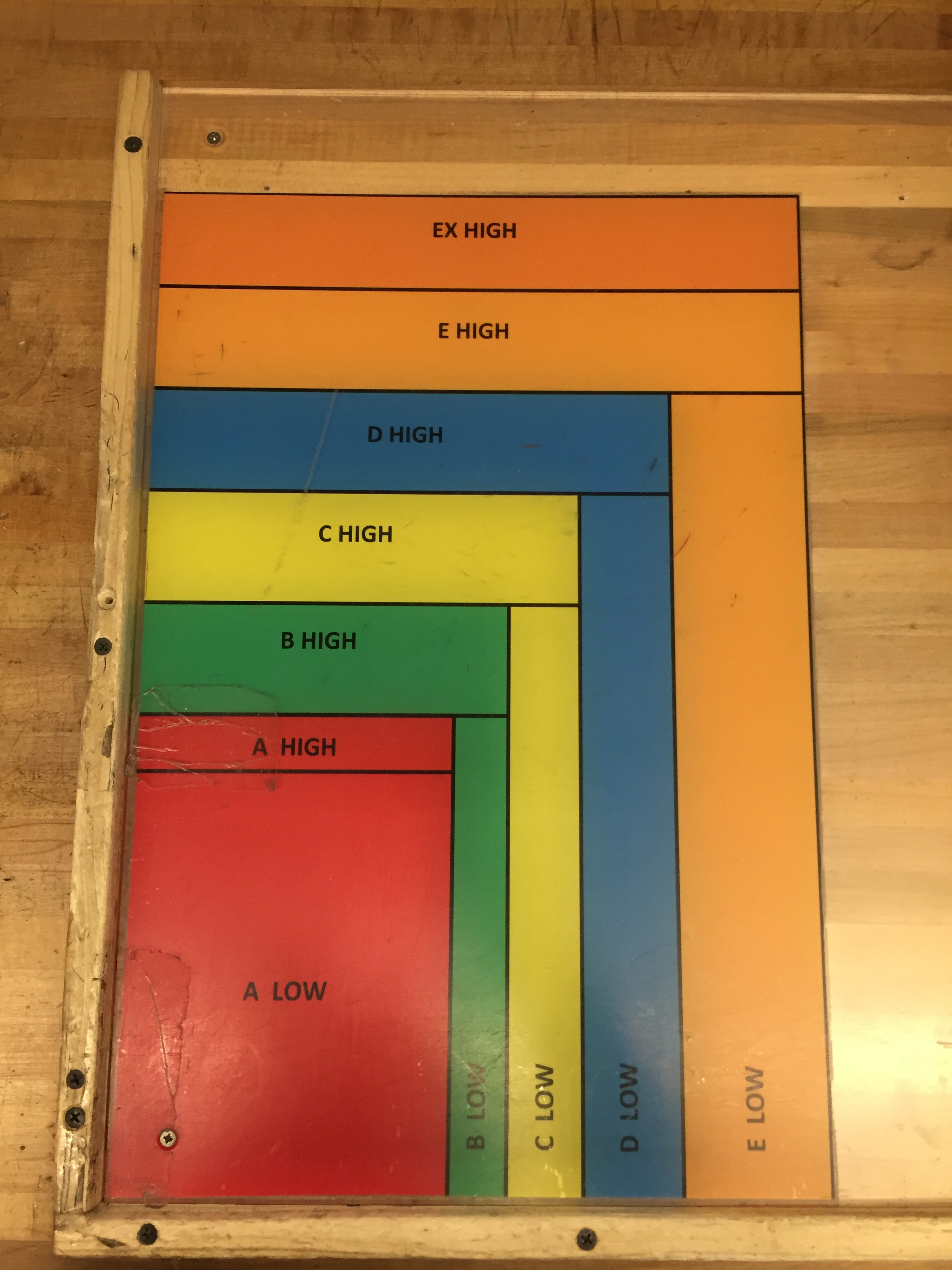

ReCAP is able to store this many items because of its size, but also the way it approaches library storage- like tetris. All senses of traditional library organizing like classification schema are thrown out the window, and in their place becomes only one metric by which materials are organized- size of the item. This is done for maximum efficiency, a concept that ReCAP takes very seriously.

Emphasis on efficiency

Once an item enters the facility, it becomes a packet of information flowing through a simultaneously complex and simple system. Items come in and out of the facility, are checked in using their barcodes, and organized by their size. Workers (because there are always people behind the movement of information) take periodic trips back into the stacks to reshelve and retrieve items, and a typical weekday consists of pulling between 600 and 700 items. ReCAP also fulfills ILL and Borrow Direct orders, of which there are approximately 20 to 30 thousand per year. The consolidation of storage and delivery of materials is another way in which ReCAP emphasizes efficiency, in that it takes much less effort to perform these tasks from a centralized location. Instead of individual library workers pulling and re-shelving materials at their own institutions, which is more time consuming and requires the labor of many more people, when it is done at ReCAP, the process is much more streamlined. Jacob notes that if large storage repositories such as ReCAP are able to do this, it frees up the time of librarians to do the intellectual work of librarianship.

In addition to implementing efficiency strategies in the workflow of moving items in and out of ReCAP, there was also significant thought put into the construction of the building, especially with regards to environmental impact. ReCAP takes up a significant portion of land, which affects water runoff and has implications for the area surrounding the facility. To mitigate their impact, a bio swale was created which helps control and direct the water runoff. ReCAP also thinks critically about their energy use, as the difference between being energy efficient and inefficient can be millions of dollars. To that end, 10% of the energy used comes from solar panels installed outside the facility, with that percentage on track to increase to 20% in the coming years. Furthermore, ReCAP is making strides to reconsider the processes of temperature and humidity control with the hopes of implementing a system that will use less energy at non-peak hours.

Library Storage Infrastructure

While visiting ReCAP, I couldn’t help but think of Shannon Mattern’s work on library infrastructures, in particular a piece about NYPL’s BookOps and ReCAP, titled “Behind New York’s Library Network” published in Motherboard. Related, I also highly recommend Shannon Mattern’s “Library as Infrastructure” article in Places Journal.

Center for Digital Humanities

After a stop for lunch, we made our way to Green Hall, located on the Princeton University campus, to visit the Center for Digital Humanities. We spoke with Jean Bauer, PhD, who is the Associate Director of the Center.

What is the Center for Digital Humanities at Princeton?

The Center for Digital Humanities is a relatively new research center that provides Princeton University graduate students and faculty with support to conduct digital humanities projects. Anyone can come into the Center for a consultation on a possible digital humanities project. In addition to full project funding, the Center offers initial travel grants and seed money to begin preliminary planning and execution of a digital humanities project. To apply for a project requires a significant application, including a data management plan, with an emphasis on making project data open and giving creative commons licenses to the data created for projects. In addition to working as project partners, the Center provides training and support in project management, grant funding, and technical skills needed to complete digital humanities projects. Jean gave the example of a current project being conducted by a graduate student, wherein the student is learning how to build a database as she works on the project. The projects that Jean mentioned to us in conversation sounded fascinating, and a list of the present projects may be found on the Center’s website.

Digital Humanities are not a service

Although it wasn’t a primary component of our discussion, I was heartened to hear Jean mention that the purpose of the Center was not to do the labor of digital humanities projects proposed by faculty, but instead work as collaborative partners throughout the project process. Furthermore, I was excited to hear about the emphasis on technical skill acquisition, project management experience, and grant application support. I was reminded of Roxanne Shirazi’s talk/article “Reproducing the Academy: Librarians and the Question of Service in the Digital Humanties” where she discusses the ways in which the work librarians do is always in service of someone else (usually a white male faculty member), and the ways in which this is problematic considering the feminized state of librarianship.

Jarrett Drake and the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library

For our final visit of the day, we stopped by the Seeley G. Mudd Library to meet with the Digital Archivist, Jarrett Drake. After a tour of the library and a quick glance at the exhibit up in the gallery about Princeton’s radio station, we sat down for an inspiring and informative walk through of Princeton’s digital accessioning workflow.

Digital Curation

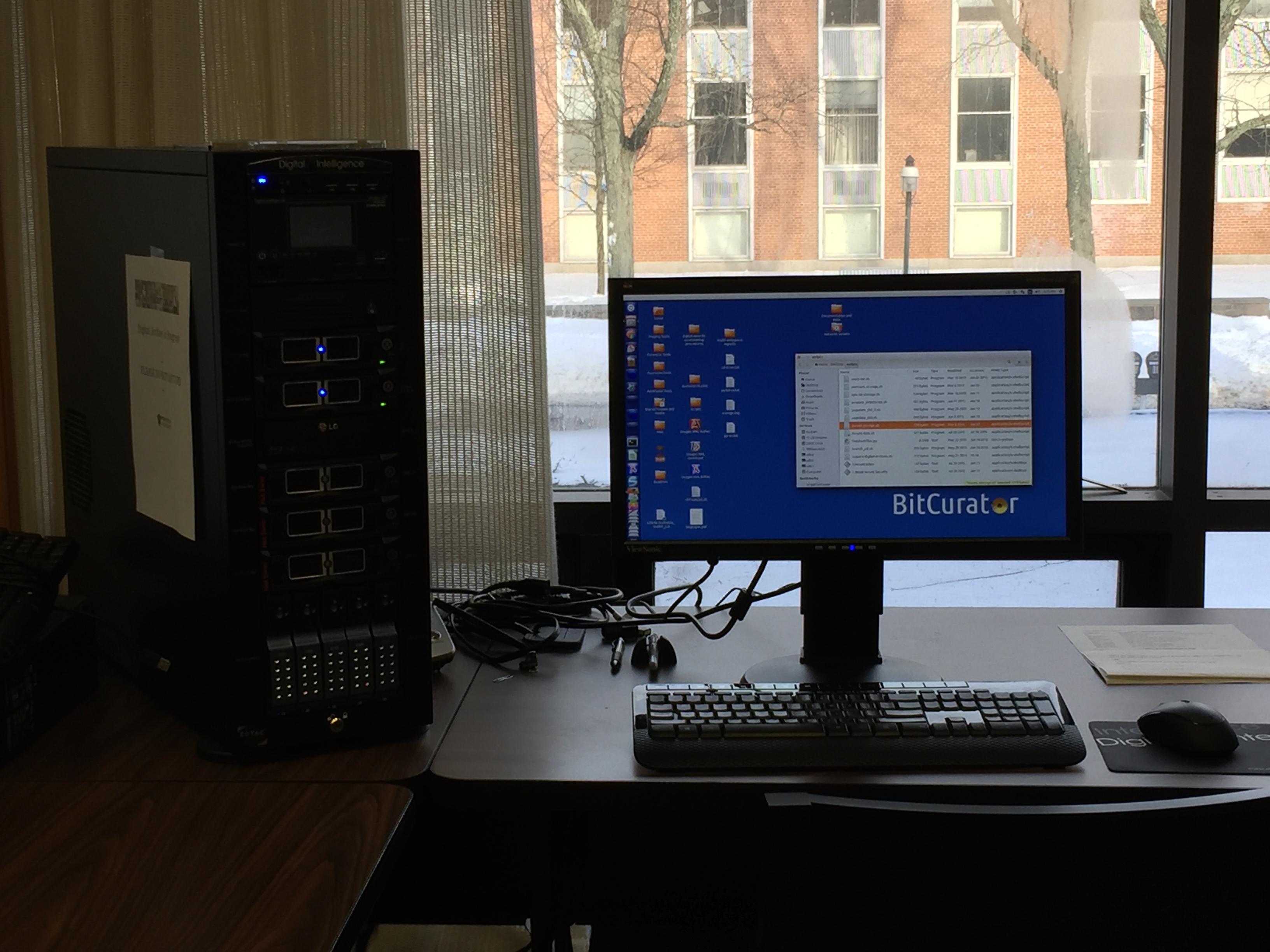

Jarrett started off with a discussion of digital curation, noting that his job as a digital archivist is about deciding what to throw away just as much as it is about figuring out how to preserve and provide access to digital materials. As we walked through the accessioning process, Jarrett mentioned using bash, rsync, the command line, and open source software such as BitCurator and DROID, to acquire and process digital materials. This was encouraging for me to hear, as I am building my skillset in this area to complete my NDSR project. His talk also confirmed that the technical experience I am gaining as an NDSR resident will only help me in my career as a digital archivist.

Princeton adheres to the MPLP, or More Product Less Process theory, which aims to do the minimal amount of processing required for a collection in order to make it accessible. While this was theory developed for paper collections, it applies to digital materials as well. Once digital files are in the archive’s care, they receive minimal processing in the form of a virus scan and unzipping of any zipped files, and then are put into an online document management system, and made accessible through a finding aid on the library’s website. If you’re curious to learn more about Princeton’s born digital workflows, you can view them online.

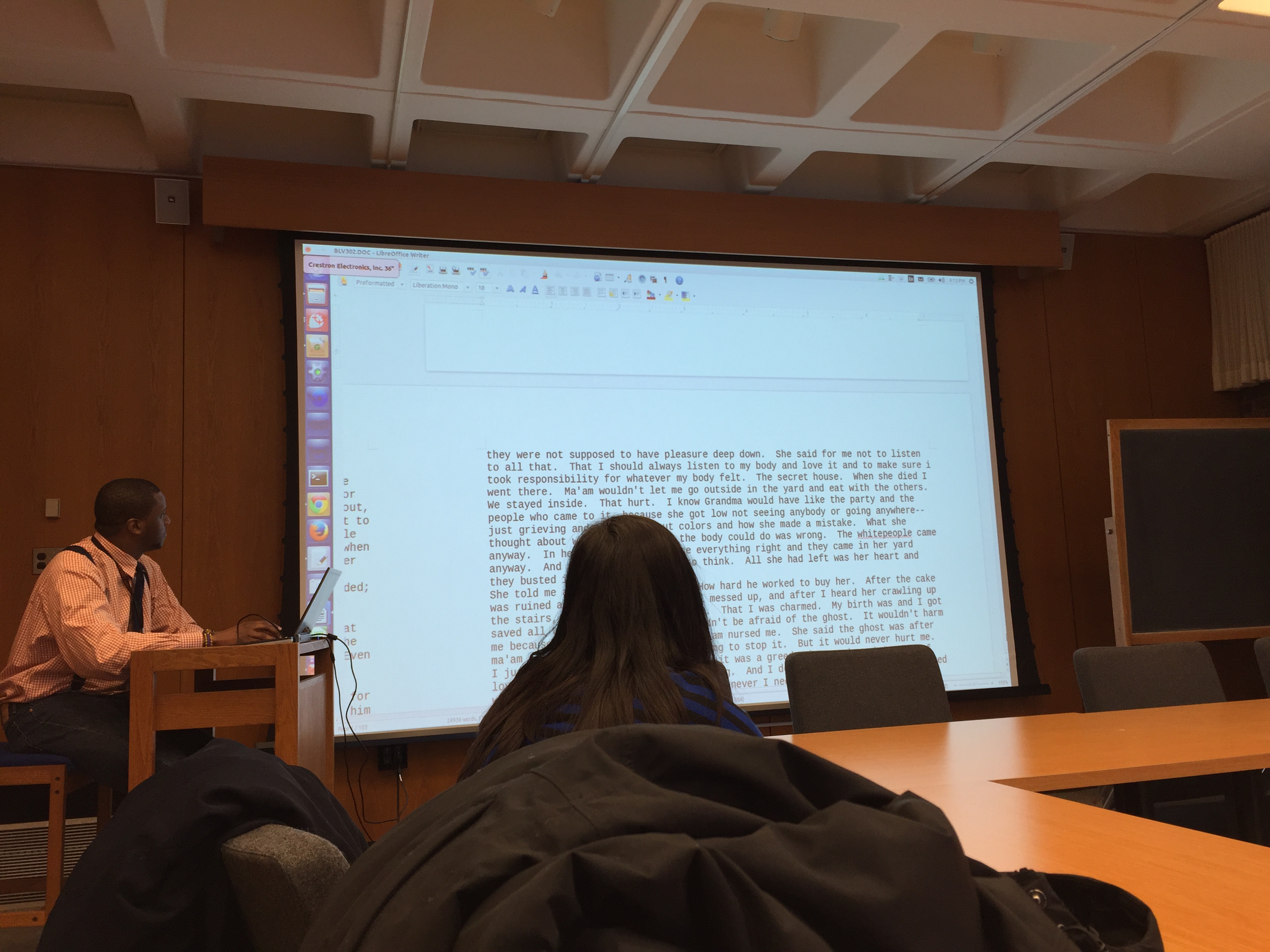

BELOVED.doc

In addition to demystifying the born digital workflow, Jarrett also showed us a draft of Beloved from the Toni Morrison papers, which lead to a conversation about getting buy-in from administration. Sometimes, it can be difficult to convey the importance of digital stewardship and digital preservation to individuals in management or administration, or even to those who are unfamiliar with the concept. Jarrett noted that the Toni Morrison floppy disks prompted a more comprehensive conversation around the topic at Princeton. It was a useful reminder for us, as we attempt to ensure that our own digital stewardship projects have longevity within our institutions.

People’s Archive of Police Violence

We also spent some time talking with Jarrett about social justice and archives, in particular a project he is involved with called the People’s Archive of Police Violence in Cleveland (PAPV). The project began as a tweet from Jarrett before the annual Society of American Archivists meeting in Cleveland this past summer. From that tweet grew a conversation among archivists about the impact they could have doing a community service project in Cleveland, in particular around police violence, an ongoing issue in Cleveland and the United States at large. PAPV partnered with a local community organization who had recorded many hours of video testimonies by Cleveland residents about their experiences with police violence, and decided to make those videos accessible online. In addition, numerous archivists in the area took to the streets to interview Cleveland residents and create an oral history collection. Following the conference, individuals volunteered to transcribe the videos and oral histories. All of the materials are accessible online, and the development of an Omeka site to host the materials is current underway. An article explaining more about the archive is forthcoming in the new Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies.

Home again, home again

After our meeting with Jarrett, we headed back home to New York. It was so great to spend the day together as a cohort, and to be able to visit with a group of individuals and organizations working in diverse capacities within digital stewardship. Meeting with Jacob and seeing ReCAP made me see that charting out a workflow for the movement of physical objects is not so different than creating one for digital objects. Our discussion with Jean at the Center for Digital Humanities showed how digitization technology can support scholarship in the humanities: for example, high quality scans allow computers to read an aggregate information from objects in ways that humans have been unable to do previously. Finally, meeting with Jarrett provided insight into the experience of working in an electronic records setting, and emphasized the need for archivists to leverage technology in service of making born digital materials readily accessible. Further, our conversation about the PAPV reminded me that the work we do as archivists is never neutral, that we should always consider whose stories we collect, and seriously consider to what extent the archives we work in represent the world around us.