Karl again! Some truly hardworking authors and editors released 2015’s National Agenda for Digital Stewardship this month. Tl;dr? Then don’t worry because I’ve got you covered. There is in fact something for everyone with a vested interest in digital preservation contained in this vision of its challenges and of the work ahead. Of course I couldn’t help but see reflections of my own project with the New York Art Resources Consortium (NYARC) throughout.

As befits an organization with the scope and mandate of the National Digital Stewardship Alliance, the agenda aspires to enable the kind of the top-down national infrastructure solutions that have been so influential to digital stewardship in the EU–especially when it comes to our biggest big data problems. Nonetheless, it promotes multi-institutional collaborations among smaller organizations like NYARC’s as the most important model for digital stewardship.

Why? Throughout the agenda, NDSA makes the case that this model: provides essential redundancies; enables specialist institutions to focus on collecting within their unique scopes; lets the same perennially under-resourced institutions punch above their weight class as teams; and, ultimately, further distributes a preservation network that by means of its interconnection can perform its longest-term functions more sustainably than can any single vendor. This is an “ecosystem” in which many more can thrive.

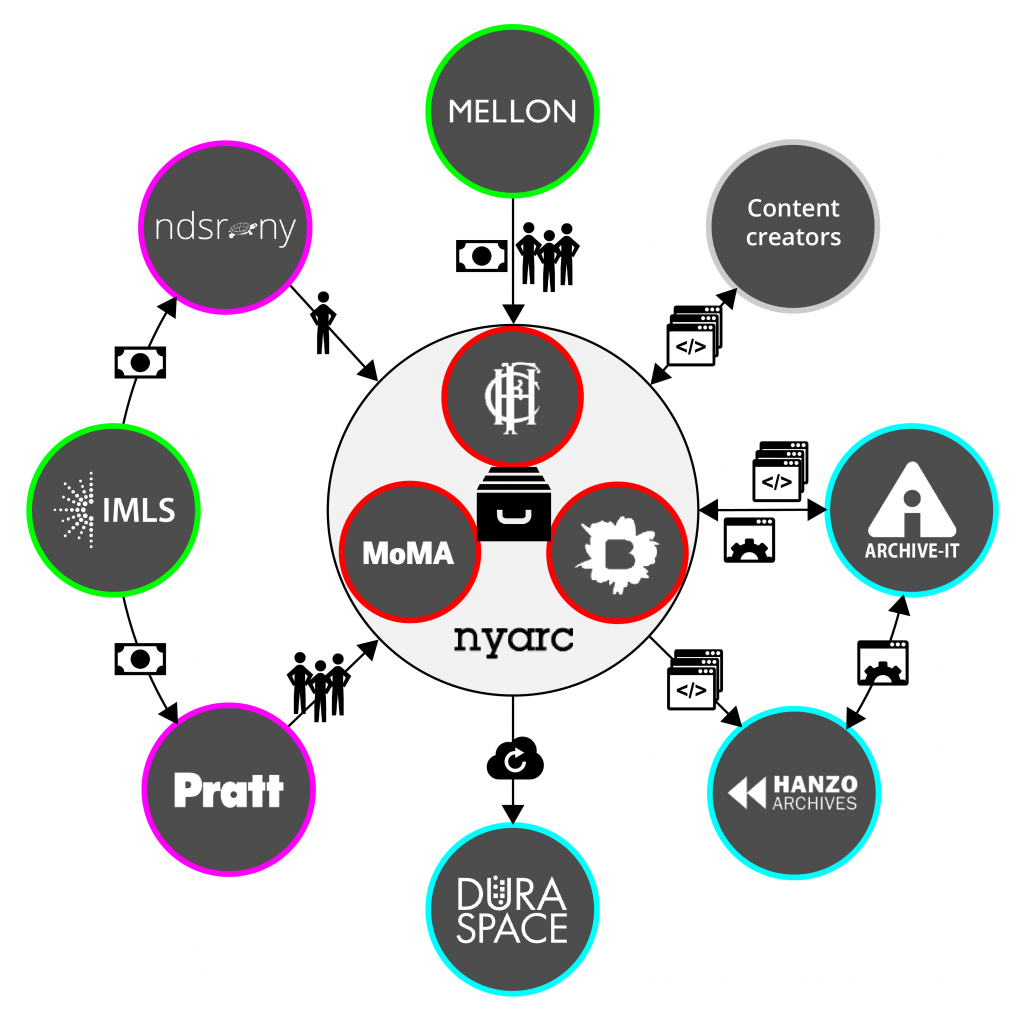

Of course that’s all easy enough to say, but much more difficult to coordinate among our respective institutions’ no less important short-term and internal requirements. Visualize just the closest circle of partners in NYARC’s very specific (and very young!) effort to archive and manage specialist art historical resources from the web, and what you get is already a fairly complex machine:

Schematic diagram of web archive management at NYARC by Karl-Rainer Blumenthal. Icons by Hello Many, Juan Pablo Bravo, and Simple Icons of The Noun Project.

The NYARC directors at the Frick Art Reference Library, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Museum of Modern Art, and their financial supporters—the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Institute for Museum and Library Services—all clearly understand that this project has to resolve the greatest inter-institutional challenges in order to lay a foundation for future collaborations. Those challenges, as articulated throughout the National Agenda, are to openly share documentation, engender buy-in from content creators in the commercial sector, and foster the next generation of digital stewards.

As Peggy succinctly demonstrated last week, implementing standards for highly specialized digital resources tends to be a difficult balance of specificity and interoperability. NYARC embraces this challenge by modeling processes for the quality assurance, preservation metadata, and archival storage of web archives among three institutions with many disciplinary affinities but great collecting diversity. This facilitates a kind of ‘instant interoperability’ to standards sufficiently specific to be practically applicable at each institution. Moreover, each institution will contribute to the project’s iterative documentation, which the wider field of art librarians will be invited to reference and develop. Watch this space for updates on that front!

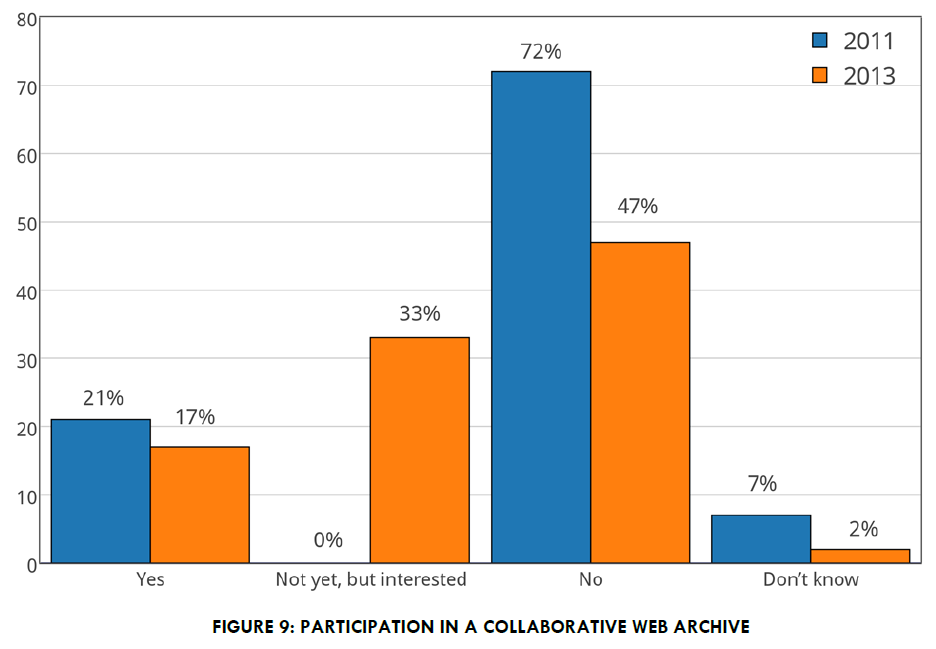

Others are certainly eager to take that baton and run with it. As the NDSA’s national survey of web archiving programs—released right on the heels of the National Agenda—indicates, resources for collaborative efforts like the Internet Archive’s Archive-It software service will support an explosion of desire to archive the web as a team:

Such projects have thus far relied on the Herculean efforts of human catalysts like NYARC’s web archiving program coordinator Sumitra Duncan. And while open documentation lightens their load significantly, we all must also do more to engage commercial actors and next-generation digital stewards to share it.

For-profit enterprises define the work of web archiving by exponentially expanding and diversifying the contents of the web, and yet they have been all-too-little engaged to shape expectations of long-term viability. NYARC closes this circle by going directly to the publishers, auction houses, galleries, and curators who create the live web, and demonstrating the program’s value not just as immediate scholarly resource, but dark archive for proprietary content with no extant preservation strategy. In so doing, it also overcomes its greatest technical obstacles with input from Hanzo Archives—a private web archiving organization whose expertise with the most challenging elements known to web design stem from its work with innovative corporate web instances. Encouraging more private concerns like these to team with heritage organizations towards long-term preservation strategies is absolutely essential to ensuring that our organizations have the intellectual resources we need to get the job done.

Perhaps most important of all to the long-term viability of all of this work, however, is the empowerment of our truly born-digital generation of information professionals to own and replenish it. I’m lucky to have a temporary view from vanguard myself, but I’m especially curious to see what NYARC’s youngest and most imaginative teammates will make of it. With the support of Mellon and IMLS, we currently enlist the support of no fewer than six interns from Pratt Institute’s Masters degree programs in Library & Information Science, Digital Art & Information, and History of Art. The students already provide critical vision to otherwise tedious tasks. Their responsibility for management and use of these resources will only increase, so the onus is on all of us to ensure in the meantime that they have a heritage worth stewarding.

Long-term preservation and shared responsibility are critical to all of us and yet notoriously difficult to articulate in value statements. If we ever want to streamline the intricately-structured, grant-funded, and highly project-specific work, however, we’ll have to make convincing cases for the return on external and internal investments in permanent infrastructure, full-time staff appointments, and further research. All together now, let’s join the structures, resources, and projects to those values to give them form.