Greetings, readers. Genevieve Havemeyer-King, here, NDS Resident at the Wildlife Conservation society. It’s hard to believe we’re only one month into our residencies! I’ve already met so many people. For the past three weeks I have been interviewing the staff of WCS’ Library and Archives, Geospatial Analysis, Education, and Exhibits and Graphic Arts departments about their workflows, routines, policies, and digital media usage. This interview and surveying process is the first of three phases in my NDSR project, which will culminate in the development of new archival workflows and the implementation of a new digital repository for the Archives. In this post I’ll introduce a few complex and exciting digital preservation challenges I’ve encountered in each department.

The Library and Archives was generous enough to serve as the guinea pig for my first interview, and Madeleine Thomson, Institutional Archivist at WCS, provided me with some insight about the history of preservation at WCS:

“The Archives was started in 1979 to preserve the institutional records of WCS, which had been founded in 1895 as the New York Zoological Society. Over time, the Archives has brought in materials from all across the institution and throughout its history – materials documenting such subjects as the activities of Society staff and leadership, the exhibition and care of animals at its zoos and aquarium, and its international wildlife conservation efforts. Because the collections document the history of zoos and aquariums, the history of New York cultural institutions, and the history of wildlife conservation, they’ve been useful to a wide range of scholars; they’ve also been a fun resource for people with fond memories of their own histories at WCS’s zoos and aquarium.

The Library and Archives holds approximately 1,200 linear feet of correspondence and subject files, as well as photographs, film and audio recordings, artwork, publications, and ephemera. In general, the collections reflect WCS’s substantial record of activities, which includes opening the Bronx Zoo in 1899, running the New York Aquarium since 1902, and, in the 1980s, assuming management of the Central Park, Prospect Park, and Queens Zoos. Along with directing these iconic New York City institutions, WCS also manages more than 500 conservation projects worldwide.”

Madeleine Thompson, Institutional Archivist and Digital Resources Manager (left); Leilani Dawson, Processing Archivist (right) in the WCS Library and Archives

Leilani Dawson, my NDSR project mentor and Processing Archivist at WCS, gave me some background on the genesis of the NDSR project. According to Dawson, over the past couple years, digital collections have continued to grow, and WCS Archive staff have begun addressing these collections in various ways, but have had limited time to split between the analog and digital collections; “The NDSR project allows us to pursue high-priority goals such as deeper collaboration with other WCS departments on their electronic records…”

I then spoke with Eric Sanderson, Senior Conservation Ecologist, and his team of spatial analysts in the GIS Lab. Using data from hundreds of maps and stored in an array of geospatial databases, the team collaborates to continue work on The Welikia Project, which involves the reconstruction and mapping of how New York City looked when Henry Hudson arrived on the scene back in 1609, and to enhance the interactive web application, Visionmaker NYC, which “allows the public to create and share…designs for Manhattan based on rapid model estimates of the water cycle, carbon cycle, biodiversity and population”.

The preservation of geospatial data from this department will be a primary focus of my project (in addition to the Visionmaker software), but it has also been an important issue in the preservation field at large, specifically for federal, state and local government agencies which depend on geospatial data for urban planning and maintaining records on urban growth, and scientific agencies such as NASA. In 2007, the Library of Congress, and state geospatial and archives staff from North Carolina, Kentucky, Montana, and Utah formed the Geospatial Multistate Archive and Preservation Partnership (GeoMAPP), which “aimed to address the preservation of “at risk” and temporally significant digital geospatial content”. Two of their reports – Best Practices for Archival Processing for Geospatial Datasets and the accompanying Archival Metadata Elements for the Preservation of Geospatial Datasets, released in 2011, have served as amazing resources for my preparation in developing an OAIS compliant workflow for processing these collections.

D-Lib Magazine recently published an article, Data Stewardship in the Earth Sciences, by Robert Downs, PhD. (et al), Senior Digital Archivist at the Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN) – a research and data center of the Earth Institute of Columbia University – and member of the former NASA Software Reuse and NASA Open Source Working Groups. An excellent primer for my interviews with the GIS team, the article (and brief phone conversation I was lucky to have with him!) provided some background on the recent history of preservation efforts and open data initiatives such as NASA’s Earth Science Data and Information Policy, which calls for open data sharing in the earth science community, and The Federation of Earth Science Information Partners (ESIP) data stewardship principles, which is establishing a standard for the provenance and context content (PCCS) that “must be preserved in order for Earth science data to be re-used for climate change studies”.

GIS data plays a part in many WCS initiatives (and conservation in general) around the world, and consideration of the current standards, practices, and conversations presented by experts in the GIS field will be integral to developing a workflow for managing data from not only the Welikia/Visionmaker GIS team, but likely will inform how the Archive receives collections from other departments as well.

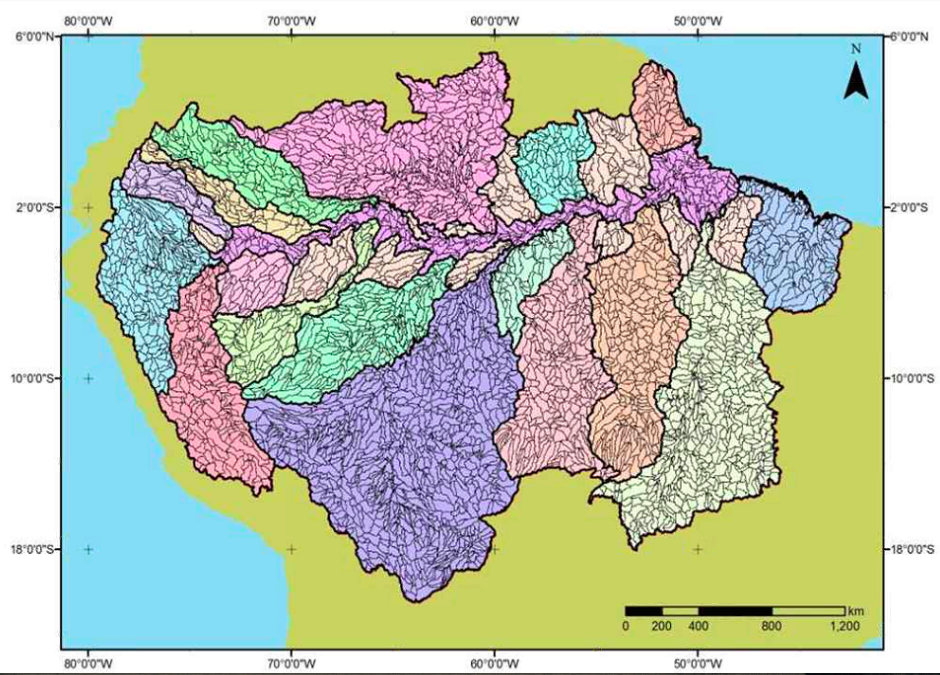

A scalable map of the entire Amazon River basin system, part of an impressive GIS database developed by field staff for the Amazon Waters Initiative, and debuted during a Lunchtime Talk presented by Dr. Julie Kunen, Executive Director, Latin America and Caribbean Program at WCS.

Within the Education Department, archiving moving image, web-based, and photographic documentation will all be crucial to preserving WCS’ rich history of outreach and collaboration with schools, governments, and the global conservation community. In particular, WCS maintains a YouTube Channel of Google Hangouts, which capture pivotal moments during their public events and educational programs. In making these videos publicly available, they are able to gauge how these activities affect and reach local and global audiences.

Erin Prada, Manager of Digital Learning and Engagement, hosting a Google Hangout during the U.S. Ivory Crush at Times Square in NYC, organized in partnership with WCS, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, NY Department of Environmental Conservation, African Wildlife Foundation, Humane Society, IFAW, NRDC, and WWF, in which 1 ton of confiscated ivory was crushed to make a statement to the ivory trade. (Ivory Crusher in background)

The educational materials, media, and analytical data combine to form rich collections of information about each educational program and initiative offered by WCS, and the challenge will be in developing a system for compiling these materials into sustainable archival packages that retain and reflect their impact.

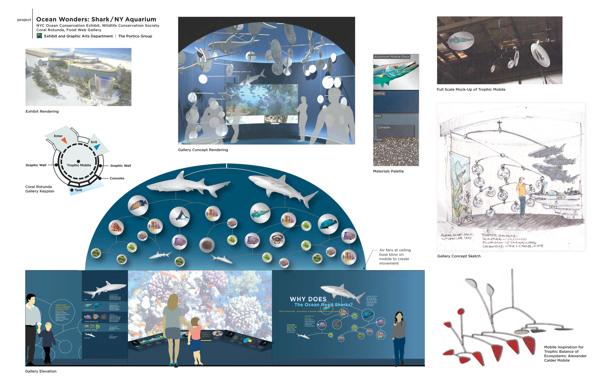

The Exhibit and Graphic Arts Department (EGAD) is responsible for the planning, engineering, architectural design, and development of graphical renderings for zoo and aquarium exhibits and WCS facilities, as well as promotional materials, signs, logos and other illustrative and graphic materials. Beautifully constructed and highly detailed, the materials they create document the history of how the Bronx Zoo and the Wildlife Conservation Society has changed over time, physically and in practice.

Tsingy Cave Exhibit conceptual illustration. (Walter Deichmann, Illustrator; Association of Zoos and Aquariums, source).

Long term preservation of their work will require a thorough understanding of standards for computer aided design and the EGAD teams’ workflows for exhibit development. Mike Ashenfelder’s comprehensive overview on the preservation of CAD data, Untangling The Knot of CAD Preservation, featured on The Signal, emphasized the importance of standards for compatibility and portability between systems, and specifically ISO 10303, the “Standard for the Exchange of Product model data” (STEP), which will be important to consider when planning for future access to these collections.

Graphical renderings of the “Ocean Wonders” exhibit and features at the NY Aquarium. Image courtesy of Naomi Pearson, EGAD at WCS.

Developing a system for balancing the needs and requirements of these different workflows and accommodating the influx of such a diverse collection of media will be quite an endeavor, but I look forward to working within this digital ecosystem and to learning from my colleagues about how it all functions together to help WCS keep its spotlight in the global conservation community.

Pingback: WCS NDSR Project Post: “The Digital Ecosystem at the Wildlife Conservation Society” | WCS Archives Blog